A 55-year-old Pakistani male presents to the emergency department with a 10-month history of numbness, tingling, and pain in both lower extremities and a 5-month history of similar symptoms in both arms. He also complains of having progressive, asymmetrical weakness in both legs, without sphincteric dysfunction, for two months. There is no history of fever, cough, diarrhea, or constipation or of joint pains, weight loss, photosensitivity, polyuria, or polydipsia. The patient is an ex-driver by occupation who has eight children and belongs to a lower socioeconomic group. He is a nonsmoker and denies alcoholism. He has had essential hypertension for five years and takes tablet bisoprolol 5 mg daily on a regular basis. Other than that, his medical history is insignificant. Family history is unremarkable.

Physical Examination and Workup

On physical examination, the patient is found to be alert and oriented to time, place, and person. The patient's oral temperature is 98.6°F. He has a regular pulse of 68 beats/minute. His blood pressure is 130/80 mm Hg, with no postural drop, and his respiratory rate is 14 breaths/minute. His Glasgow Coma Scale score is 15. His cranial nerves are intact and symmetrical. He has a left foot drop and paraparesis with areflexia and bilateral mute plantar response. (Figure 1)

The patient also has a bilateral glove-and-stocking loss of sensations in the upper and lower extremities, with normal perianal sensation, and a high-stepping gait. Signs of meningeal irritation are absent. His abdomen is soft and nontender. There is no clinical evidence of palpable masses, organomegaly, or ascites. His bowel sounds are audible. The patient's precordial examination reveals normal heart sounds. Auscultation of the lung fields reveals normal breath sounds bilaterally.

Laboratory analysis demonstrates a normal complete blood count (CBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Liver function tests, renal function tests, serum glucose level, muscle enzymes, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph are unremarkable. His nerve conduction studies and electromyography are consistent with a chronic demyelinating polyneuropathy. (Figure 2)

Lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is performed, revealing a mildly elevated protein level of 0.52 g/L. All other CSF studies are normal. His hemoglobin A1C, thyroid function tests, and serum B-12 levels are normal. Results for antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, HIV serology, hepatitis B surface antigens, and hepatitis C antibodies are negative. Computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is unremarkable. His bone marrow biopsy, bone scan, skeletal survey, and urine test for Bence-Jones protein are negative. His serum protein electrophoresis reveals a discrete, narrow spike in the gamma-globulin region of 1.96 g/L, consistent with monoclonal protein (M-protein; also called paraprotein), and serum immunoglobulin-M (IgM) levels are markedly raised at 13.6 g/L (normal range 0.4-2.3 g/L). (Figure 3)

Based on the history, physical examination, and workup, what is the likely diagnosis?

These neuropathies most often affect men over age 50 years. Patients usually present with sensory symptoms such as numbness, paresthesia, dysesthesia, and aching or lancinating pain, with these predominantly involving the lower extremities. Touch, joint position, and vibratory sensation are mostly affected. Gait difficulties, imbalance, and ataxia progress over a period of months. Weakness of the distal leg muscles with variable atrophy occurs as the disease progresses. A pure motor disorder simulating motor neuron disease is seen in a very small number of patients.

The literature shows that peripheral neuropathy associated with IgM monoclonal gammopathy presents mainly as a chronic demyelinating sensory polyneuropathy, with predominant tremor, sensory loss, and ataxia. Polyneuropathies reported in association with multiple myeloma or with IgG or IgA monoclonal gammopathy are more heterogeneous (mainly axonal or mixed).

The study of MGUS neuropathy has been confounded by its relation to chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), with about one quarter of patients with CIDP also having a paraproteinemia. However, the meaning of this association is unclear. Conduction blocks, which are the cardinal electromyographic feature of CIDP, sometimes occur in MGUS as well, and the CSF protein level is usually elevated in both conditions. Moreover, both neuropathies respond to immunomodulating treatments. However, IgM paraproteinemic neuropathies are more refractory to therapy. In some cases, monoclonal gammopathy is a coincidental finding and is unrelated to a patient’s neuropathy.

The optimal therapy for MGUS neuropathies has not been established. About one third of patients with IgG or IgA MGUS improve symptomatically within days or weeks of the administration of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; 0.4 g/kg of body weight daily for 5 days), plasma exchange (a total of 220 mL/kg, given in 4 or 5 treatments), or therapy with corticosteroids, often in combination with immunosuppressants.[25] However, only the benefit of plasma exchange has been confirmed in a controlled clinical trial.

Although the IgM neuropathies tend to be the most refractory to therapy, some improvement can be expected with the same regimens used for the IgG and IgA neuropathies, particularly if cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil is added in doses sufficient to reduce the amount of M-protein.

An alternative treatment in paraproteinemic neuropathies is immunoadsorption, but its role has not been fully substantiated through trials. Interferon alfa was beneficial in one trial.[31] However, these treatments generally produce only transient improvement and require repetition every several months, depending on the patient’s response and general condition.

Which is most common type of M-protein associated with MGUS-associated neuropathy?

The presence of which of the following will favor the diagnosis of multiple myeloma rather than MGUS?

A 69-year-old woman presents with neutropenic fever and painful skin lesions. She has a past medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome, neutropenia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cirrhosis. The skin lesions began 2 weeks prior as small nodules that progressed to painful, red plaques. At that time, they were present on her back, left breast, and right posterior calf. She also experienced fevers up to 102°F (38.9°C) over the last week. She describes having shortness of breath with myalgias over the last few weeks, in addition to a more recent onset of cough, nausea, and diarrhea. She has no lesions in her mouth or her genitals and reports no vision changes. Her myelodysplastic syndrome has been treated with azacitidine, which she last received 3 weeks prior. She has a right internal jugular port-a-cath, in which a needle was recently dislodged. She has not had any pain since that time.

Upon physical examination, the patient was noticeably short of breath. The site around her port was not erythematous, warm, or tender, and no drainage was observed. A 4- to 5-cm erythematous, edematous plaque was present on her back. It was warm and tender with some overlying crust.

A similar plaque was seen on her right posterior calf, and her chest had erythematous and tender papules. She had a low-grade fever (100.4°F [38°C]) and tachypnea (25/min). She was pancytopenic, with a white blood cell count of 1.5 x 109/L and an absolute neutrophil count of 0.3 x 109/L. Her platelet count was 10 x 109/L. Upon admission, her hemoglobin level was 6 g/dL, and she required 2 U packed red blood cells. Chest radiograph findings were unremarkable.

Which of the following is the most appropriate initial test to evaluate the nature of the patient’s skin lesions?

A punch biopsy was performed on the plaque on her right calf, and the specimens were sent for histopathologic examination. A portion was sent for tissue cultures. Hematoxylin and eosin stain findings revealed mild spongiosis and acanthosis, as well as papillary dermal edema. The dermis also contained patchy perivascular inflammation, which was variably lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic. Abundant extravasated red blood cells were noted. Special stain results were negative for infectious agents. The tissue was cultured for bacteria, fungus, acid-fast bacteria, and nocardia. No growth was observed on any of the culture plates after 1 month.

Based only on these findings, which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

Which histopathologic finding is most characteristic of Sweet syndrome?

Which of the following is considered a major diagnostic criteria for Sweet syndrome?

Which of the following is the most appropriate treatment for Sweet syndrome?

Hint

A 1-year-old boy presents to the pediatrician with his parents reporting frequent infections, bruising, and decreased activity. Past medical and family history are unremarkable. He has taken no medications, and his vaccinations are up to date. The parents report no known allergies. He lives with both parents, and he attends daycare 5 days per week.

What is the most appropriate next step in this patient’s management?

HLA typing was ordered as part of the routine diagnostic workup. Some patients with JMML develop cytogenetic or clinical findings that require hematopoietic stem cell transplantion (HSCT). The initial result of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing was an error result, followed by an indeterminate result. ABO blood typing identified two distinct red blood cell populations (group B and group O) with genotyping and phenotyping discrepancy.

Which of the following is the most likely cause of this unusual ABO result?

Clinical manifestations of chimerism include having multiple hair textures, skin colors, and/or eye colors; being ambidextrous; and having abnormal sexual development. Chimerism is also associated with a higher incidence of autoimmune disorders and, possibly, transgender identity, although the latter association is not without controversy. A proportion of apparently phenotypically normal patients may experience reduced fertility.

Which of the following is NOT a potential phenotypic manifestation of genetic chimerism?

Chimerism may also result in unexpected results on DNA testing such as maternity/paternity testing or forensic examinations. Unusual results of blood or HLA typing should be investigated with additional laboratory testing to identify the exact typing and to rule out chimerism. This is key for donors of blood, stem cells, and other tissues because chimerism may alter risk for rejection or other complications.

What are the best next steps for this patient?

HSCT may be required in some patients with JMML, particularly those who develop cytogenetic or clinical findings. A key component for donors of blood, stem cells and other tissues is that unusual results of blood or HLA typing should be investigated with further laboratory testing in order to identify the exact typing and to rule out chimerism, which can alter rejection risk or other complications. Donor testing for HSCT should entail molecular techniques rather than standard HLA typing methods.

What would be the best next steps for this patient if he requires HSCT?

A 30-year-old pregnant woman presents to the clinic with repeated vomiting episodes unrelated to meals. She experienced hematemesis 2 weeks ago, which lasted 1 day. Since this event, she has been experiencing severe heartburn and epigastric pain not relieved by over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors. She had been retching the week before the hematemesis and also had repeated occasions of severe nonbloody projectile vomiting, which were controlled by antiemetics. The patient is in her third trimester (35 weeks' gestation, first pregnancy). She experienced severe vomiting during her first trimester, but this subsided with symptomatic treatment (antiemetics) and change of diet. She has a daily multivitamin but frequently forgets to take it. Which of these tests is most important to order for this patient?

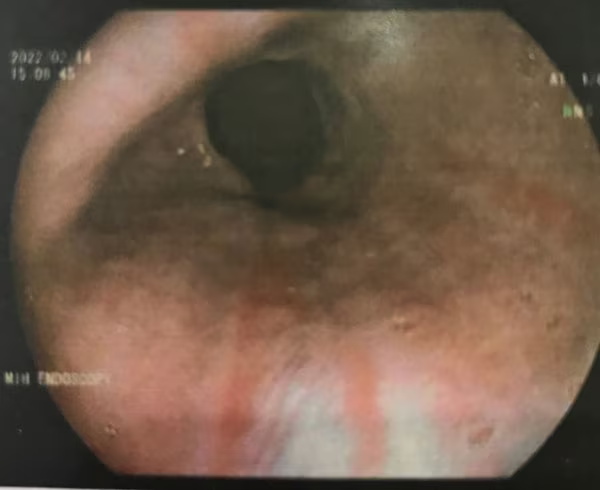

The patient's blood pressure was found to be normal, which excludes preeclampsia, so upper endoscopy is the logical next step for establishing the location and etiology of her bleeding. In normal circumstances, elective procedures should be postponed until after delivery, and nonemergent procedures should be performed in the second trimester (with special attention to fetal monitoring and left uterine displacement). Although this patient is in her third trimester of pregnancy, upper endoscopy is merited because it is an urgent case. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy shows healing linear tears of the lower esophagus (Figure 1). Which of these is the most likely diagnosis?

Figure 1. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing healing linear tears of the lower esophagus.

Figure 1. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing healing linear tears of the lower esophagus.

MWS tears are usually treated conservatively with acid suppression or endoscopic hemostasis because most cases resolve without recurrence. However, a bleeding tendency due to chronic vascular or organ dysfunction can increase bleeding from the MWS lesion or even mask the lesion. Which of these is the most common comorbidity associated with MWS?

What is the most common position of MWS tears?

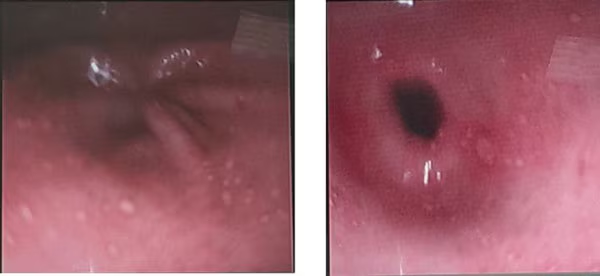

The patient received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) infusion for 72 hours and was then instructed to continue an oral PPI for another 2 months. The condition was relieved and her symptoms improved. However, 2 weeks later, the patient again began experiencing severe epigastric pain not relieved by PPI therapy. The physician recommended repeat endoscopy, which showed multiple small ulcerations in a linear pattern in the antrum, with hyperemic mucosa bleeding easily upon contact with the endoscope (Figure 3). Biopsy samples were obtained for histopathologic examination, which confirmed gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Viral DNA was isolated from the gastric tissue and appeared on histopathology as purple intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies. Immunohistochemistry staining is superior to standard hematoxylin and eosin staining in diagnosing CMV infection of tissue. After discussion, the patient opted for treatment with valacyclovir to avoid fetal CMV infection. CMV is the most common congenital infection globally, affecting 0.5-2.5% of newborns. Congenital complications caused by vertical CMV include hearing loss, chronic eye inflammation, epilepsy, and neurologic and intellectual deficits. After primary maternal CMV infection, the risk for vertical transmission rises with gestational age: about 30% in the first trimester and 70% by the third trimester. The earlier the transmission, the greater the health consequences for the child after birth. In a 2023 Italian cohort of pregnant women with CMV infection (447 patients in 10 centers), valacyclovir treatment decreased the rate of congenital CMV transmission at the time of amniocentesis (but not at the time of birth), the rate of symptomatic congenital CMV infection at birth, and the rate of pregnancy termination. However, there are no current official guidelines for treating CMV infection in pregnancy, and no drugs are currently approved for this indication. CMV is part of the Herpesviridae family. Approximately 30% of immunocompromised patients with CMV infection develop gastrointestinal involvement. CMV can affect both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals with variation of the gastrointestinal involvement, where infection can extend to affect the whole gut from esophagus to colon. In a retrospective cohort study of more than 356 patients with biopsy-proven gastrointestinal CMV infection, the inpatient morality rate was 21%, and CMV enteritis had the highest rate, at 23%. Which of these is the best option for treating CMV infection in this patient?

Figure 3. Endoscopy showing multiple small ulcerations in a linear pattern in the antrum, with hyperemic mucosa bleeding easily upon contact with the endoscope.

Figure 3. Endoscopy showing multiple small ulcerations in a linear pattern in the antrum, with hyperemic mucosa bleeding easily upon contact with the endoscope.